If I were a betting woman, I’d be willing to bet that you didn’t learn the word schema in school, especially as an intermediate student, but that’s exactly what I’m going to be advocating in this post: the explicit teaching of not only the word schema, but also the application of it in the classroom. So, what is it? What does schema actually mean? Let’s unpack it.

Schema is, essentially, the technical term for prior knowledge. It is everything you know and remember inside of your brain. It is, at it’s very core, a foundation that all learning is built upon—indefinitely. Forever and ever. Amen.

Because it is so foundational, I like to start out my reading strategy instruction with lessons on schema and metacognition (thinking about your thinking). I have found that once students grasp how their brains function, how to monitor their own thinking, and grasp how they are continually adding to their memory storehouse (or schema), they become more intentional, purposeful readers.

Teach Metacognition First

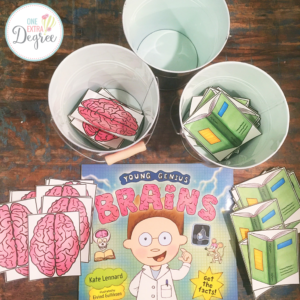

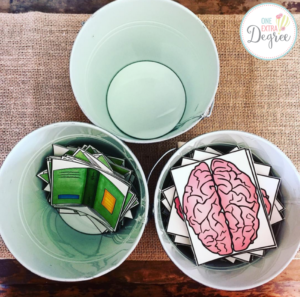

Metacognition is a really big, fancy-sounding word. I always emphasize how BIG and important it is by writing it on a sentence strip and displaying it on the whiteboard. I explain that metacognition is a big word, like a college word, and it is at the very core of everything we do in school. I break the word into parts and explain what each root—like cogn— means, and I explain that it means “thinking about your thinking”. Then I demonstrate what metacognition looks like as I read and interact with a text. I have done this a few different ways over the years, but this year, I decided to switch things up, to make it more obvious. I filled two bucket contained book cards and another contained brain cards. The brain cards represent what I know-my schema. The book cards represent what I am reading in the text– the words on the page. I want kids to observe the way I think about my thinking. Whenever I read the text, I put a book card into a third bucket. Whenever I activate my schema, I share it aloud and place it into the third bucket.

Anchor Student Learning with Anchor Charts

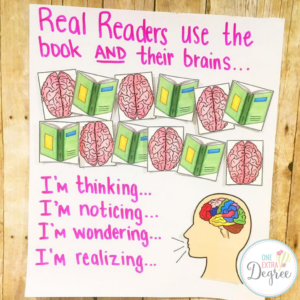

At the end, I pull the cards out of the third bucket and attach them to an anchor chart to show how I relied on my brain and the book to make meaning as I read aloud, then we will discuss the process and how schema can help us as readers. Students are able to visually see how I relied on my brain and the book as I read the text. I used to attach ALL of the cards to the chart, and I still might in the future. For this chart, I only displayed a few of them to leave room for thinking stems to help facilitate accountable talk and meaningful discussions. Even if you just display a few cards, you will want to emphasize how many cards were placed into the buckets, and you will want to explicitly point out how you were able to make meaning while reading because you were reading what the words said and you were relying on things you already know to make sense of it.

Explicitly Teach the Language of Metacognition

Explain that whenever you think while you read, your brain lights up and you activate different areas of your brain so they can do very important tasks like remembering or storing information. Show them the colorful brain. (I placed mine inside of a dry-erase sleeve and mounted it on black construction paper so it looks more-or-less like a brain scan.) Is this an oversimplification? Sure, although your brain does light up when activated, it doesn’t look like this, exactly. This particular image shows the different lobes of the brain though, and that’s a great way to show that we want to light up the whole brain. If desired, you can always pull up an image of a real brain scan to project onto a screen and provide scientific evidence of how amazing our brains are.

Demonstrate rereading a few pages and thinking aloud as you hold up the lit-up brain. Say things like, “I wonder… I’m thinking… This reminds me…” etc. Point out when you ask a question, predict, etc. Name it. Practice it. Repeat it. Sooner or later, your students will own it. Students can practice this with a self-selected text and a partner using these fun props and thinking stem strips!

Schema: It’s What We Know

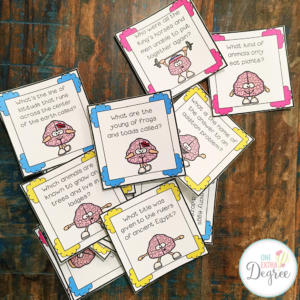

Once I introduce the process of metacognition, I forge ahead with schema lessons. Trivia is a fun way to test our memory and our knowledge of miscellaneous facts, so it’s a great introduction to schema. As I read questions aloud, I ask students to write their answers to each question on their whiteboards. I may asking these questions: “How did you know the answer? When did you learn that? Were there any questions that were unfamiliar? Do you think everyone knew the answers to every question? Why would there be variety in the answers we wrote on our whiteboards?” The human brain is an amazing organ that helps us remember information. This information is stored in the brain and becomes our prior knowledge, or schema. We are able to activate the brain and retrieve information that is stored there to complete tasks. Amazing!

I am always a big fan of scavenger hunts or any activity that gets kids out of their seats, so a Schema Scavenger Hunt is a great way to reinforce this in a fun way. They can walk around the room and fill out a fact they know about each topic. Once they complete their recording sheet, they return to their seats to share out their prior knowledge, or schema, with others!

Fire Those Neurons

Whenever connections are made, neurons fire inside of our brains. They are like little messenger cells that help communicate information to other cells. So, I thought, wouldn’t it be fun to share information while firing (throwing) a little plush neuron around the room to make this concept come to life? I bought the Giant Microbes Brain Cell Neuron Plush Toy from Amazon, and I was far too excited to receive this gray guy in the mail. Isn’t he glorious?

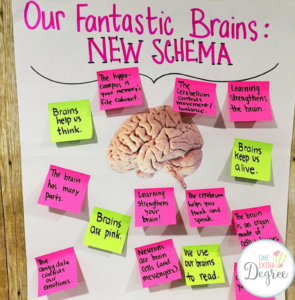

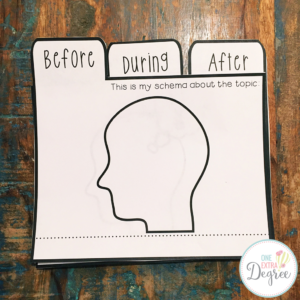

Charting Our Growing Schemas

You can create a simple anchor chart to show that we are always activating our brains to retrieve what we already know, but we are also always adding to our schemas as we learn new information about topics. Prior to reading, ask students to tell you what they know about a topic and write them in a certain color or on a particular color of Post-It. Then, after reading, have students write in (or on) a different color. It’s a quick and simple way to make this concept visual.

Practicing Thinking Aloud

If you want to give your students extra practice thinking aloud about what they know and what they learned (and know NOW), you can use thought bubbles. A simple way to do this is to use a dry erase board. I found a premade board at Walmart many moons ago that I have used for demonstrations with students, but you can easily draw a thought bubble on a board and write a thinking stem inside of it. Depending on how permanent you want this to be, you can use a dry-erase marker or a Sharpie!

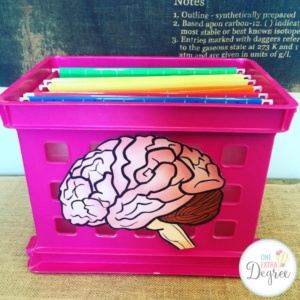

Your Brain is a Filing Cabinet

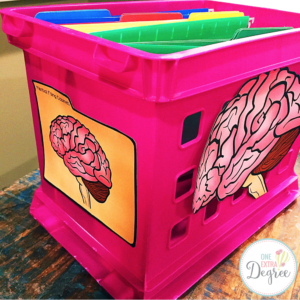

I have been using the “your brain is a filing cabinet” analogy for years, and usually I would pull a drawer out to retrieve a file to make my point. It was effective, but I couldn’t help but wonder, “Could it be more visual for kids?” As it turns out, there is a better way! I simply tacked a brain and a label onto a pink locker crate, and viola! It’s a brain/filing cabinet! (I do like to show my students pictures of dendrites too. I draw pictures of them on the board and talk through a few topics, drawing branches to group information. I explain that those tree-like branches are like files in a file cabinet, and it’s evidence that learning actually causes our brains to grow and change! In file cabinets, we can see the growth and change as files are added as well!) We also sing a song about schema that helps students internalize what schema is and how it works like a cabinet in their brain.

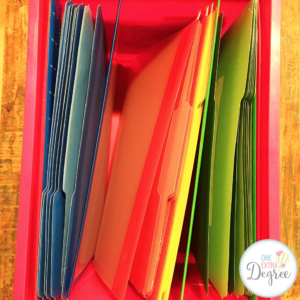

This concrete model makes the whole concept of how a brain stores information visual. Your brain is the ultimate container. It holds a massive amount of information, and it manages to organize all of the information it receives in a way that makes it accessible and easy to retrieve. To illustrate this, I placed color-coded hanging files inside of the crate. Each hanging file contained a coordinating folder. Inside of each folder, you can place coordinating paper or Post-its by topic. So, one hanging file might be about domestic dogs. Each folder could house coordinating paper with information about a particular breed.

The folders allow an opportunity to discuss how sometimes we remember something incorrectly. Basically, it’s like our brain put the wrong file in the wrong hanging file. You can demonstrate this with the colored folders, and then show how we can reorganize the information, clarify the fact, and file it correctly, just like a filing cabinet.

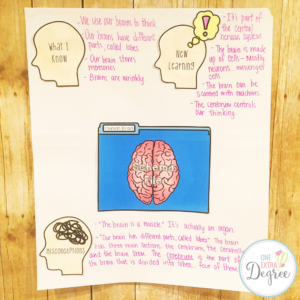

Charting Schema, New Schema, and Misconceptions

Once students are aware of schema, new schema, and misconceptions, we build an anchor chart as we interact with text to demonstrate how this works in action. We chart what they know about a topic first, then chart the new facts they learned as they read, and finally we tackle the misconceptions. We discuss how misconceptions are part of being human and part of the learning process. The important thing is to clarify and correct our misunderstandings–to refile the information.

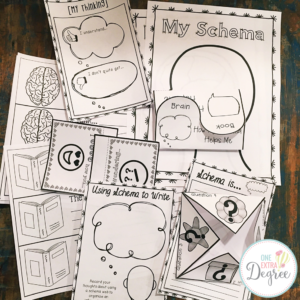

Opportunities for Independent Practice

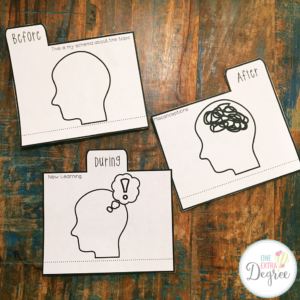

In any Reader’s Workshop setting, it is imperative that students have an opportunity to practice independently as part of the Gradual Release of Responsibility model. After the guided practice component and chart-building, students read a self-selected text and record information onto a file folder interactive notebook template.

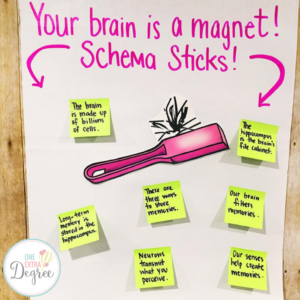

Schema Sticks with You

I have done so many variations of this lesson over the years. If you searched my blog, you could find a somewhat creepy anchor chart showing a girl’s face/head covered in squares of tissue to demonstrate how your schema is inside of your head and how it “sticks with you”. It may have been a little off-beat, but it worked, and my students understood the concept. I also previously used a lint roller as a concrete model, but I wanted something different and perhaps, if possible, more technical.

Then, it dawned on me that the brain is like a magnet because it pulls in a ton of information. So, I cut up some of the pipe-cleaners in my word work drawers so that they were just little stubs. Then I placed them inside of a 2-liter bottle. When I moved a magnetic wand over the bottle, the pipe cleaners clung to the side. I was so excited to see how it formed little branches like dendrites. It totally reinforced the concept I talked about during my file cabinet lesson and builds upon the little sketches on the board. Ultimately, I ditched the bottle, and I liked the visual even better.

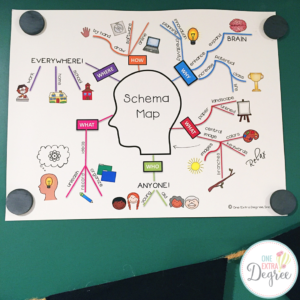

Using Schema Mapping When We Write

Schema maps mimic the actual organization of the brain. Each branch continues to branch off into smaller, connected topics, just like dendrites. You will need to walk students through the color-coding and chunking of the information, but I cannot say enough about this strategy. I love how it visually shows connections and information, but what has amazed me over the years, is how well my students remember information after mapping. I recall one guided social studies lesson a few years back. We weren’t doing anything super fancy. We were using our social studies text (which we rarely did), and we were mapping information about Ohio Native American tribes. I was modeling on chart paper, and my students were mapping at their desks. I did a quick recap the next day before moving on, and it was ridiculous how much information they recalled, including not only tribal names, characteristics, weapons, and who lived in wigwams or longhouses. It is powerful, friends!

In this lesson, I teach the organization of a schema map using an example, then students help me create one using a short, shared text, and eventually, they create their own before writing about a topic of their choice. It is the perfect culmination to the unit on schema and metacognition, because the main goal of every strategy lesson is student implementation, and writing is such a critical part of being about to demonstrate understanding.

Student Accountability

Although this unit relies on a lot of concrete models, games, and fun activities, there has to be student accountability. I believe that we should always have somewhat of a paper trail for documentation. So, this unit utilizes graphic organizers, recording sheets, interactive notebook templates, a reading passage, a song, and formative assessments to give students an opportunity to create a record of their learning.

Concrete Comprehension: Schema and Metacognition

Do you want to try this dynamic and powerful unit with your own students!? Check out Concrete Comprehension: Schema and Metacognition for Intermediate Students! This intermediate unit focuses on schema and metacognition to lay a firm foundation for strategy instruction! It includes five mini-lessons that progress from a teaching point, to explicit instruction, guided practice, independent practice, and a closing/extension. Concrete models are incorporated to help students better understand how the brain works, all while learning about the brain using the following texts: “Your Fantastic Elastic Brain” by JoAnn Deak, PhD., “The Brain” by Russell Freedman, and “Young Genuis: Brains” by Kate Lennard. (You may opt to substitute these texts with any text, particularly informational texts; however.) Students will engage in hands-on, visual, concrete activities that will help students literally grasp what schema is and how it can help them as readers and writers!

Beginning with a concrete experience makes thinking visible, creates strong connections, and anchors future learning . It provides students with experiences that become safety nets and promote risk-taking. Concrete models support less-developed readers and stretch proficient readers to think metaphorically. This product series engages kids’ senses through concrete, hands-on lessons, works through the gradual release of responsibility model, and gives kids time to interact with texts in authentic and purposeful ways. It is designed to engage students in literacy experiences that will promote higher-order thinking and improve their comprehension skills. While the lessons are scripted for convenience, they can certainly be used as a guide and in whichever way works best for your students. My hope is that you and your students enjoy launching your comprehension lessons in unique ways that ultimately promote rich discussion and thinking within the classroom!

Where can I get all the materials for these lessons on Schema? I want to use it in my classroom.

Hi, Jennifer! I am sorry for the delayed response. Life has been a whirlwind this year, and my blog has had to take a back-seat as I take care of some family and health issues. That said, you can find the resources for my schema unit here: https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/Concrete-Comprehension-Schema-and-Metacognition-Intermediate-2828321?aref=e4agrqlo. I also have a questioning unit that is similar, and I am currently plugging away at one for inferring, if you are interested. Take care! I hope you enjoy this unit!

Where can I get these handouts?

Hi Amanda,

I just wanted to take a moment to thank you for providing this amazing resource. It’s so important for children to have a concrete understanding of schema, and yet it’s such an abstract concept! You have made meta-cognition super concrete and easy to understand. I am so excited to share this resource with the rest of my team.

Thanks again,

Tracy